Atlas Phaenogamia or the Atlas of Mimetic Flowering Plants

- posted in

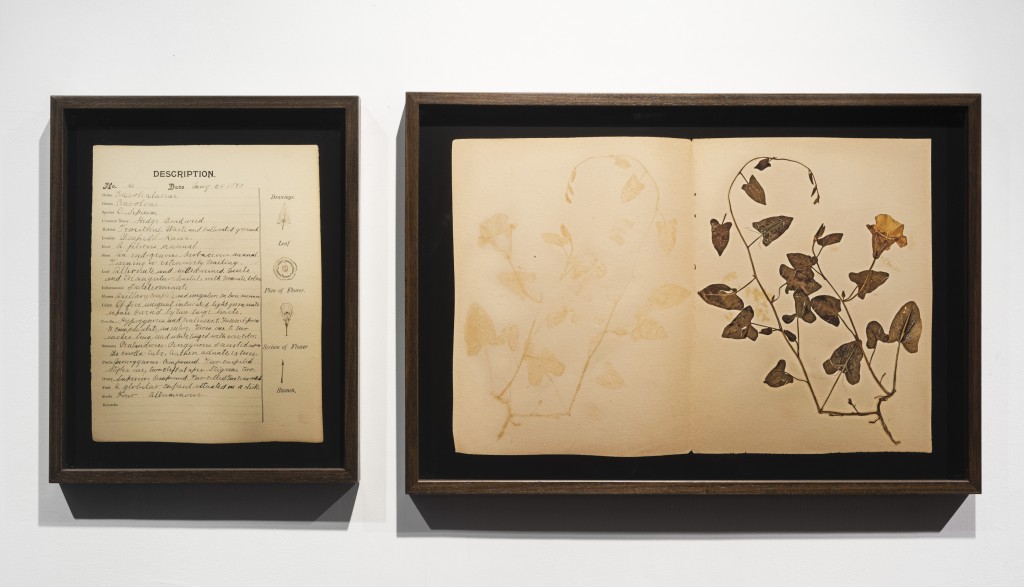

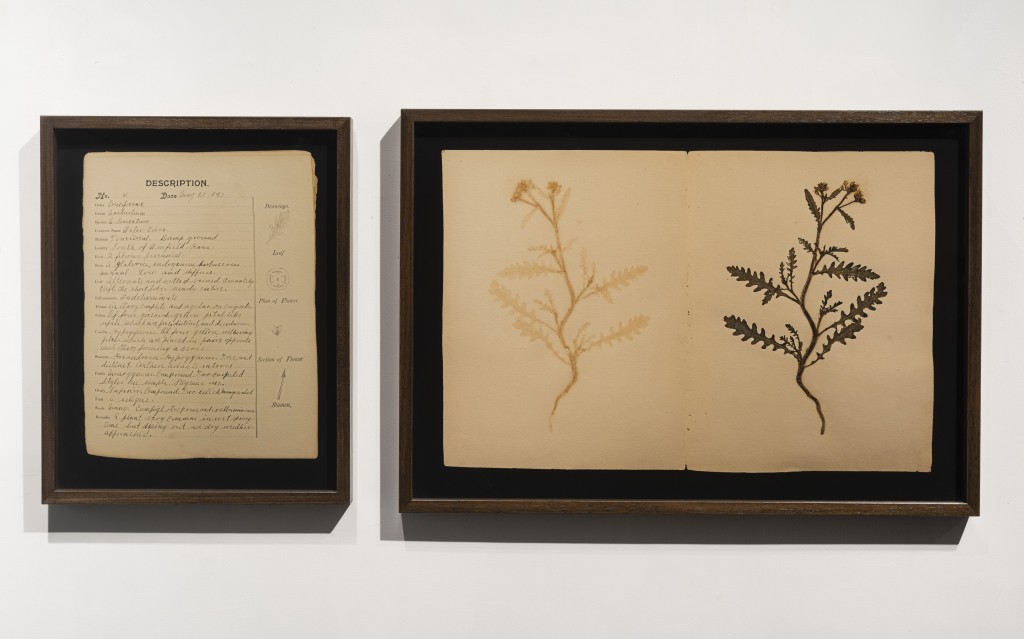

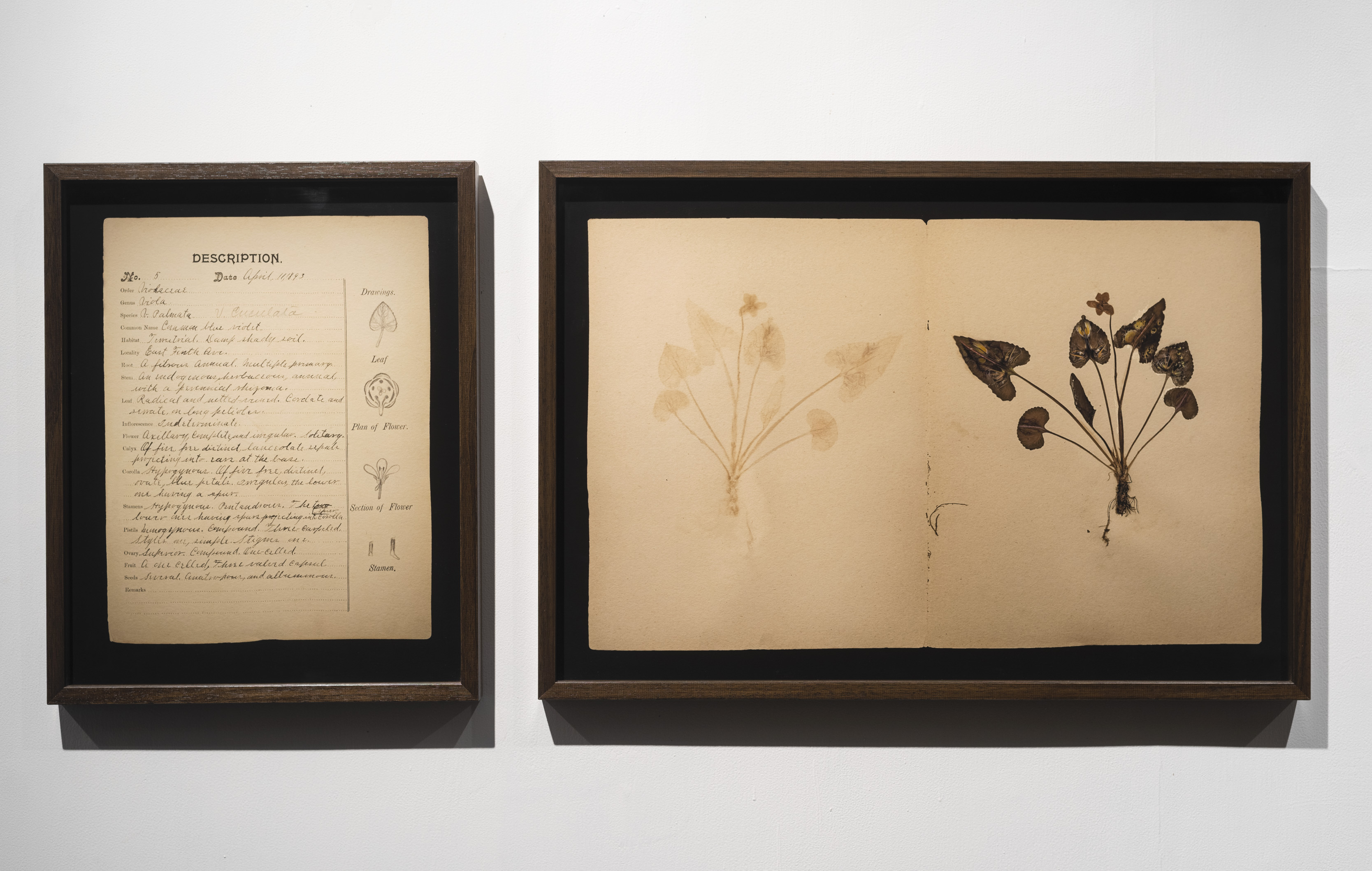

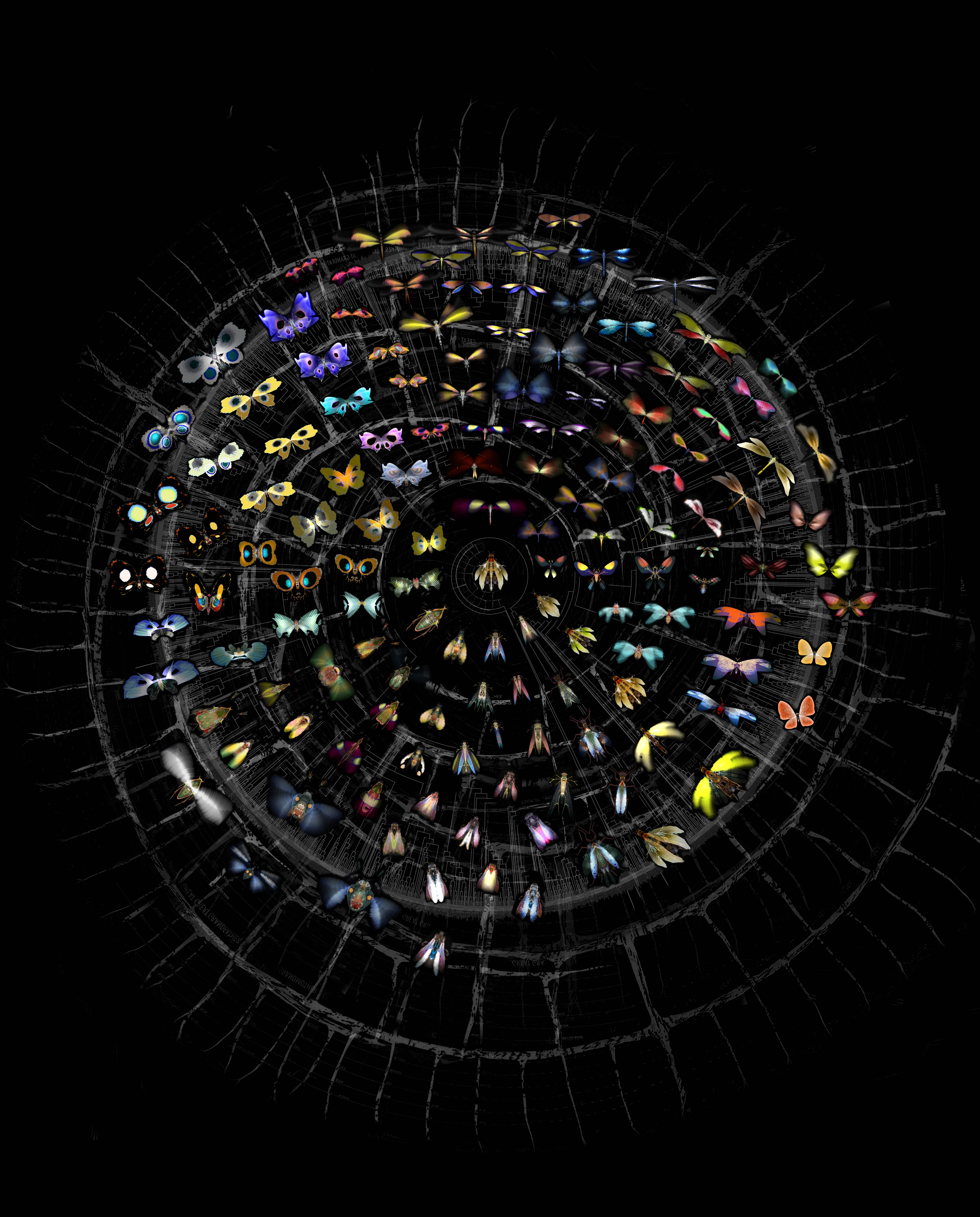

Atlas Phaenogamia or the Atlas of Mimetic Flowering Plants | installation view | image credit Anil Rane, courtesy Project 88, Mumbai

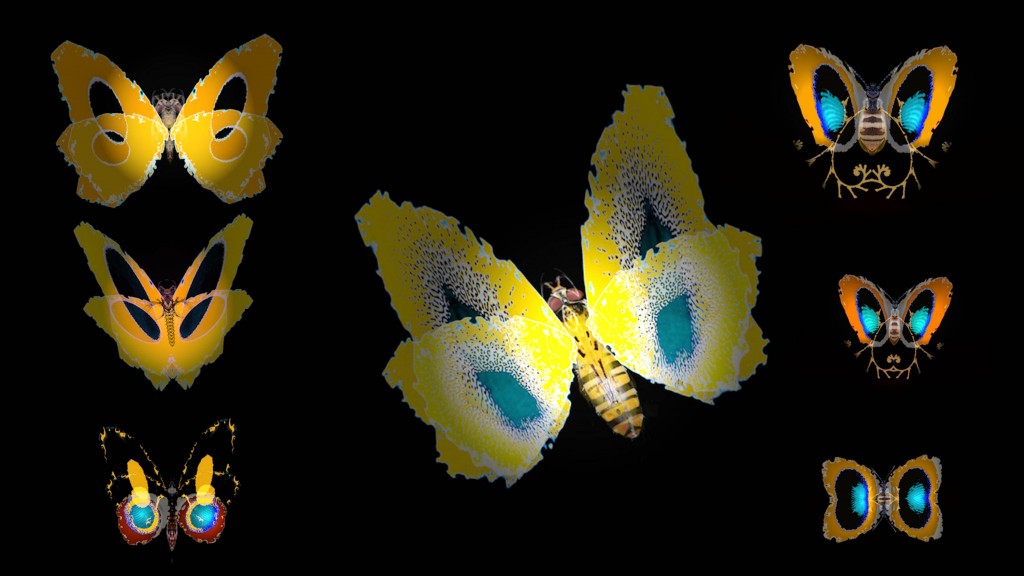

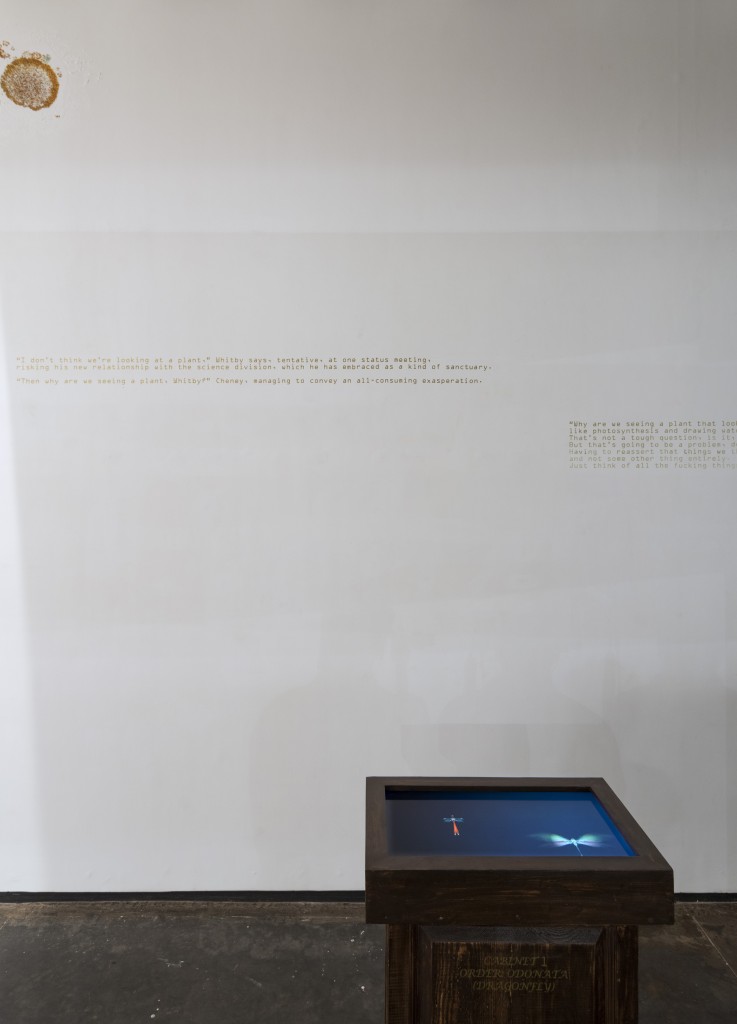

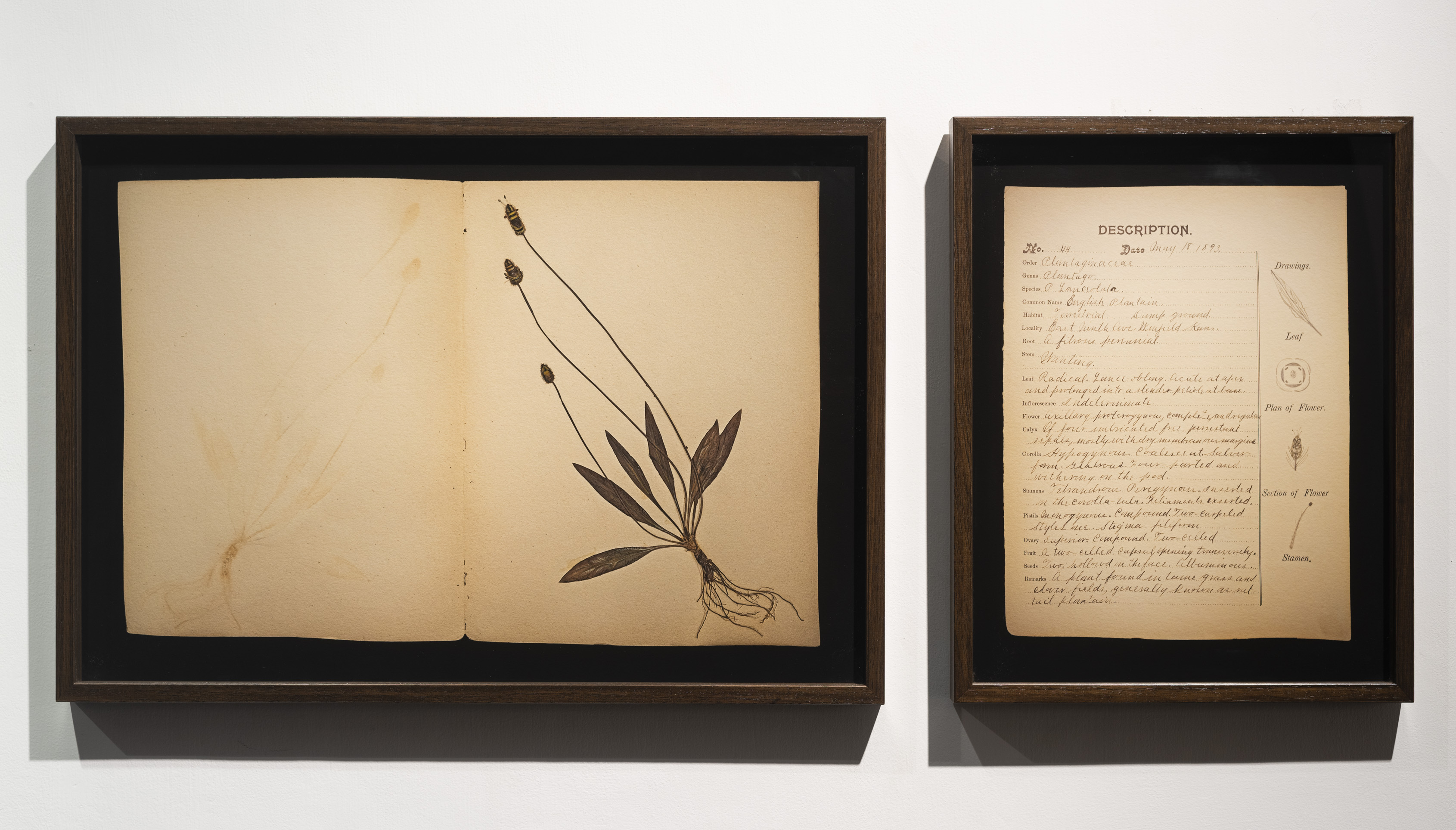

Each page of The Atlas of Mimetic Flowering Plants is both mirror and mimic, a mirror to its self and a mimic to diverse species including snake, butterfly, cicada, bee, spider, frog etc. The Atlas uses as its base selections from the series Herbarium and Plant Description, issued by the Biological Department of Southwest Kansas College in Winfield, Kansas. Dated April or May 1893, unknown collector, specimens on deposit at the R.L. McGregor Herbarium, reproduced here with permission. The R. L. McGregor Herbarium houses approximately 400,000 vascular plant specimens. The majority of these comprise exsiccatae, but the collection also includes seed, boxed, and fluid-preserved specimens. The collection is focused on the Central Grassland region of North America, with specimens from the Great Plains comprising approximately two-thirds of the collection.

Page 5 of the Atlas Phaenogamia or the Atlas of Mimetic Flowering Plants | installation view | image credit Anil Rane, courtesy Project 88, Mumbai

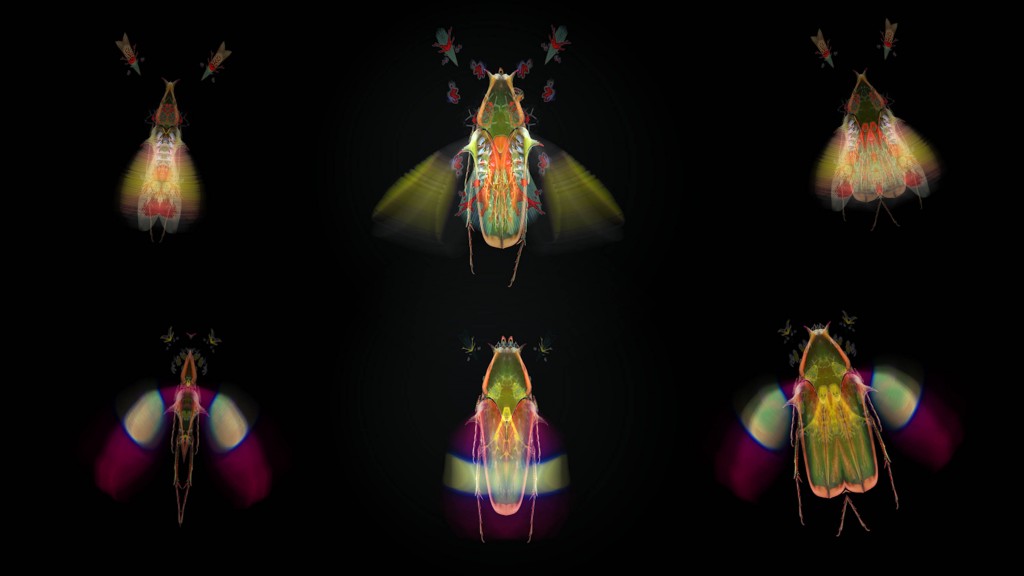

Page 1 of the Atlas Phaenogamia or the Atlas of Mimetic Flowering Plants | installation view | image credit Anil Rane, courtesy Project 88, Mumbai

- (detail) Page 1 of the Atlas Phaenogamia or the Atlas of Mimetic Flowering Plants | installation view | image credit Anil Rane, courtesy Project 88, Mumbai

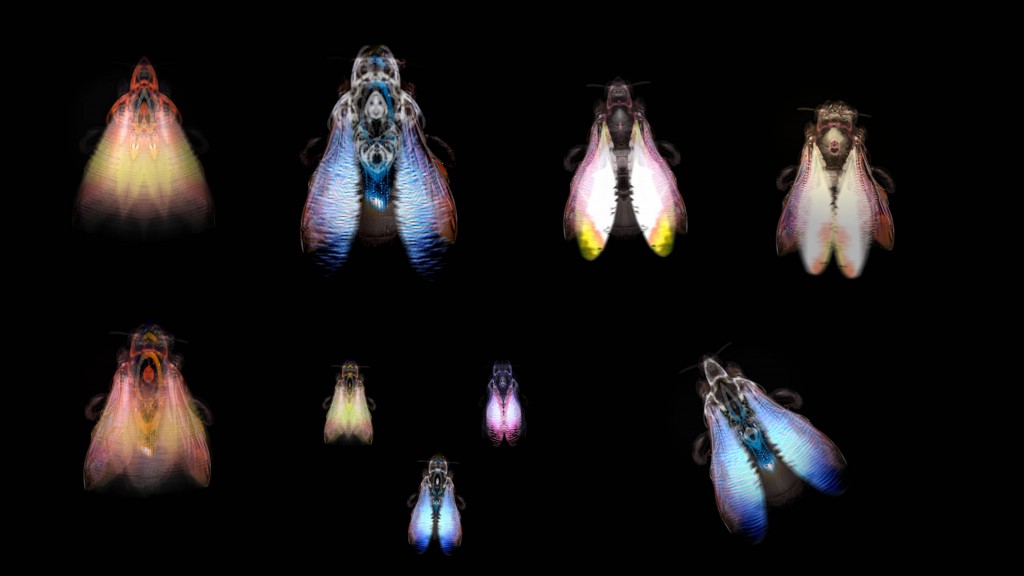

- (detail) Page 5 of the Atlas Phaenogamia or the Atlas of Mimetic Flowering Plants | installation view | image credit Anil Rane, courtesy Project 88, Mumbai

- Atlas Phaenogamia or the Atlas of Mimetic Flowering Plants | installation view | image credit Anil Rane, courtesy Project 88, Mumbai

- Atlas Phaenogamia or the Atlas of Mimetic Flowering Plants | installation view | image credit Anil Rane, courtesy Project 88, Mumbai

- Atlas Phaenogamia or the Atlas of Mimetic Flowering Plants | installation view | image credit Anil Rane, courtesy Project 88, Mumbai

- Page3 of the Atlas Phaenogamia or the Atlas of Mimetic Flowering Plants | installation view | image credit Anil Rane, courtesy Project 88, Mumbai